Polish Pyramids? Massive megalithic tombs discovered in Western Pomerania, Poland

While it has been quite some time since such a study and restoration work was conducted, these new findings have shown that there are at least a dozen huge megalithic tombs in the area near Dolice, Western Pomerania, in Poland.

These longitudinal structures, which run parallel to the ground floor, were discovered by archaeologists from the University of Szczecin, and belief them to be the handiwork of the Funnelbeaker Culture who dwelt in the proximate area from circa 4300 BC– 2800 BC.

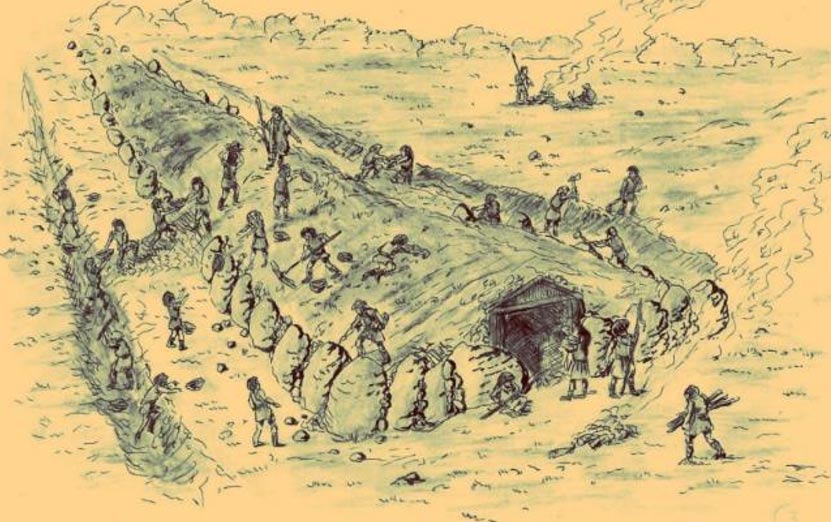

As for the ‘pyramid’ analogy, the overview plan of each tomb resembles an extended triangle. So while their heights stood at only around 3 m (or 10 ft) – which is a far cry from their Egyptian or Mayan counterparts, the ground-kissing tombs encompassed impressive lengths of about 150 m (492.1 ft), while demonstrating variable widths ranging from 6-15 m (20 to 50 ft).

When it comes to developing technology and tools, the Funnelbeaker culture is known for ‘merging’ the expertise of local neolithic and mesolithic people residing between the lower Elbe and middle Vistula rivers.

In fact, they are known for propelling the scope of agriculture and animal husbandry, which led to farming being the major source of food production in the contemporary period, as opposed to hunting and gathering. And as was the trend with every advanced culture of its time, the Funnelbeaker community invested heavily in burial methods and traditions.

Initially, these burial structures only comprised cairns made of wooden frames that were plunged into elongated barrows. But later on, these components evolved into specially constructed passage graves and dolmens.

Unsurprisingly, given the Funnelbeaker culture’s limited tools and constructional capacity (in relation to logistics), the extended triangular tombs were only reserved for the elite members of the community.

But unfortunately, when it comes to Poland, many of these megalithic tombs tend to be only preserved in forest areas. That is because, over time, various agricultural lands had invaded such megalithic grounds – an archaeological scope made even more precarious due to Poland’s status in medieval times as the farming heartland of Europe.

However this time around, the researchers have made use of advanced technological applications to identify these elongated triangular tombs, including digital terrain models or DTM (based on ALS or airborne laser scanning). As Dr Agnieszka Matuszewska, from the Department of Archaeology, University of Szczecin said –

The potential of this method is huge. First of all, it allowed to precisely locate previously known megalithic objects and, importantly, discover previously completely unknown tombs.

It is also possible to verify in the field all, even slightly preserved objects. As a result, we were able to identify them and document the degree of destruction.

This is particularly important considering the aspect of the protection and conservation of forest areas, in particular the protection of monuments with their own landscape forms.

Now it should be noted that other than the Dolice specimens, the archaeologists have also (previously) identified Polish megalithic tombs at Skronie Forest near Kołobrzeg and at a site near Płoszkowo.

Moreover, the most famous of these ‘Polish pyramids’ were discovered in Sarnów and Wietrzychowice, and their original shapes were even reconstructed following detailed archaeological research.

Lastly (and pretty intriguingly), the date of the constructions of these Dolice megalithic tombs sort-of coincides with the initial building-phase of the Stonehenge in Britain (in late 4th millennium BC) – a renowned structure that can be associated with its fair share of human burials.

And if we stretch the ambit a bit, the advent of 4th millennium BC also saw a ‘spurt’ of other ambitious projects for megalithic monuments all around Europe – possibly due to some tremendous socio-political change.