Radar Reveals an Ancient Artifacts & Treasure in Scandinavia’s First Viking City

Archaeologist have been busy excavating beneath the streets of Ribe, the first Viking city ever established in Scandinavia, and have found a treasure trove of ancient artifacts.

Ribe, which can be discovered in west Denmark, is the subject of important new research that is known as the Northern Emporium Project, which is currently being conducted by archaeologistfrom Aarhus University and the Southwest Jutland Museum.

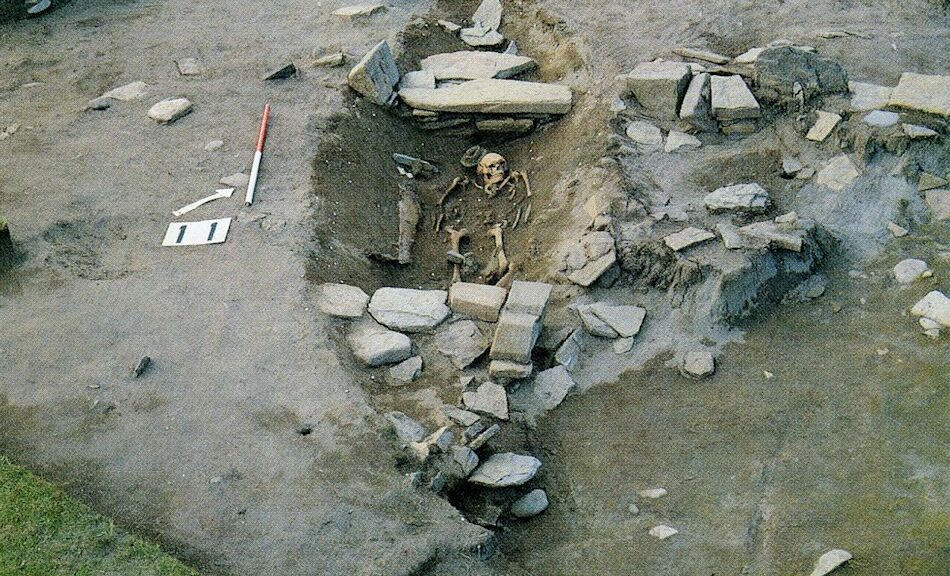

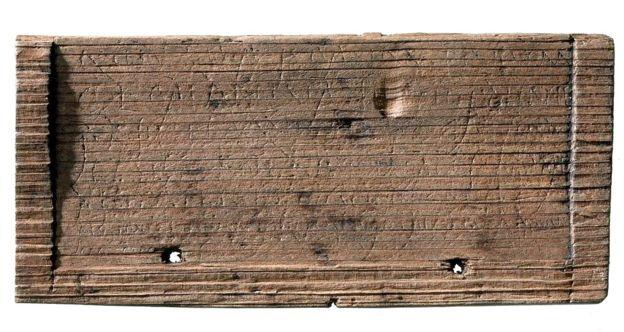

After digging just 10 feet beneath this ancient Viking city, archaeologists found thousands of artifacts such as coins, amulets, beads, bones and even combs. Lyres (ancient string instruments) have also been discovered, with some still having their tuning pegs attached to them, Science Nordic reports.

However, besides the numerous artifacts that have been excavated, archaeologist were also keen to learn more about how the city of Ribe would have originally been created.

After all, none of the people who originally inhabited this site had ever lived in a city before, and the population would have consisted of lyrists, craftsmen, seafarers, innkeepers, and tradesmen.

While archaeologists have known about Ribe for quite some time, excavating this site’s was another matter entirely. Due to high costs and the amount of time required, up until recently, only small sections of this city were investigated.

However, now that the Carlsberg Foundation has joined in, the funding for the project has been taken care of, and archaeologist are using 3D laser surveying techniques in combination with the study of soil chemistry and DNA analysis to learn much more about the first Viking’s city in Scandinavia.

Archaeologists found that not long after the creation of Ribe, houses had been built on the site which shows that this city quickly developed its residents, and would have been a largely urban community.

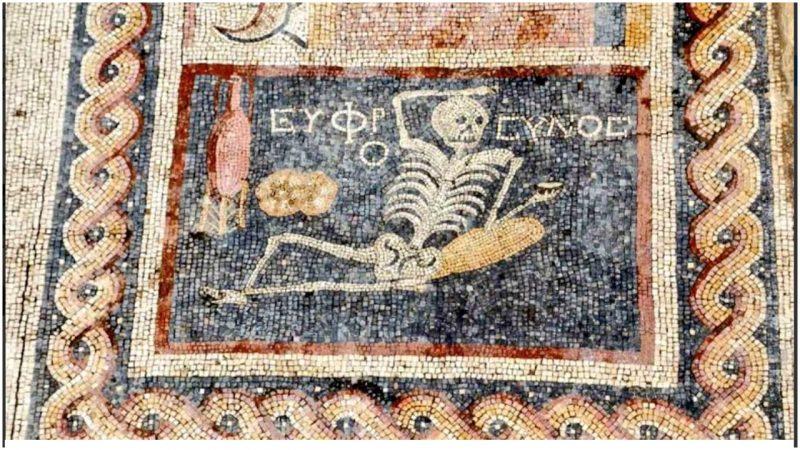

When it comes to ancient cities that existed in the Middle East and the Mediterranean, cities were packed tightly together, yet here in Ribe, the closest city would have easily been 100’s of miles away.

However, archaeologist believe that despite such great distances, the earliest settlers of this Viking city would still have traversed great distances in order to network with others.

It was also determined that as 800 AD is when the Viking era is asserted to have truly started, Ribe would have been part of what is known as the sailing revolutions.

With this new era, archaeologist noted many changes in the artifacts that were found. For instance, craftsmen who made beads originally had quite small workshops that may have only been used for a matter of weeks.

During the height of the Viking’s age, the production of these beads appears to have slowed down immensely, and archaeologist spotted evidence of other imported Middle Eastern beads that would have taken their place.

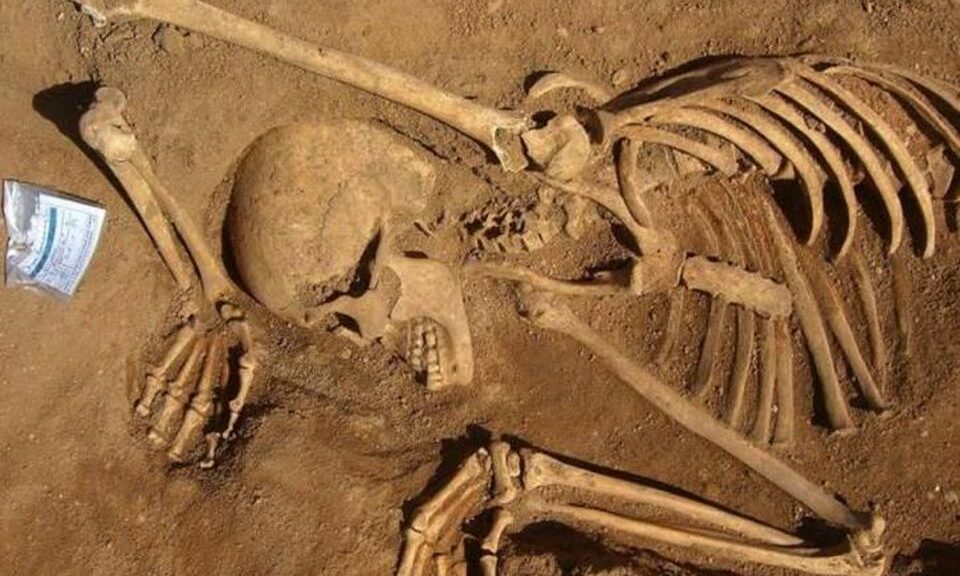

It was also found that gemstones weren’t that important to residents of Ribe. Gold, on the other hand, certainly was, and it is believed that much of the gold in use during the early days of this city would have been stolen from Roman graves.

With around 330 feet of the 1st Viking city excavated, archaeologists are progressing steadily with their study of Ribe and will continue to publicize their finds in the upcoming years.