‘Entire Streets’ Of Roman London Uncovered

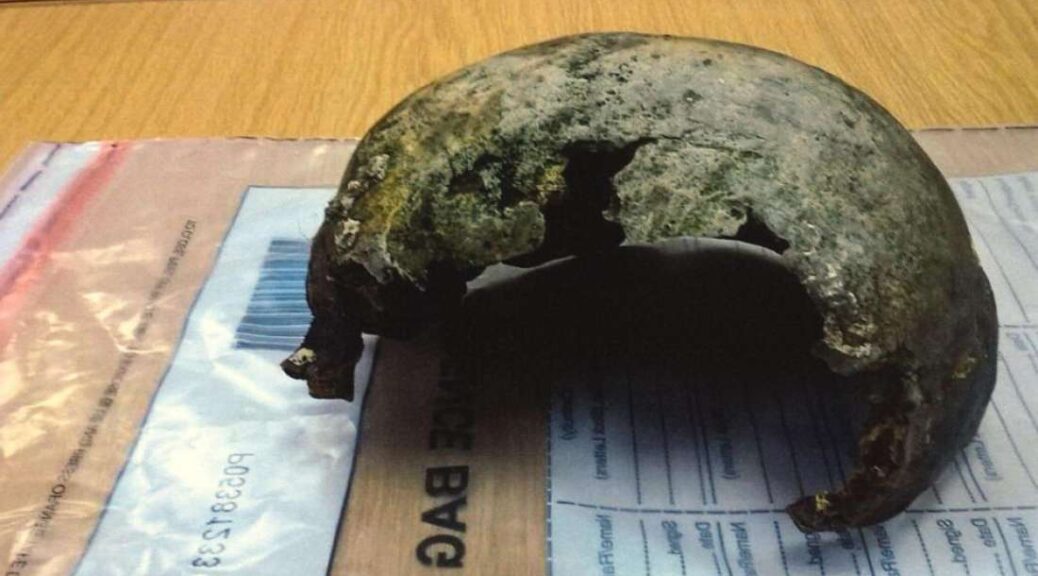

About 10,000 finds have been discovered, including writing tablets and good luck charms. The area has been dubbed the “Pompeii of the north” due to the perfect preservation of organic artefacts such as leather and wood.

One expert said: “This is the site that we have been dreaming of for 20 years.”

Archaeologists expect the finds, at the three-acre site, to provide the earliest foundation date for Roman London, currently AD 47.

The site will house media corporation Bloomberg’s European headquarters.

It contains the bed of the Walbrook, one of the “lost” rivers of London, and features built-up soil waterfronts and timber structures, including a complex Roman drainage system used to discharge waste from industrial buildings.

Organic materials such as leather and wood were preserved in an anaerobic environment, due to the bed being waterlogged.

‘Beautifully preserved’

Museum of London archaeologists (MOLA), who led the excavation of the site, says it contains the largest collection of small finds ever recovered on a single site in London, covering a period from the AD 40s to the early 5th Century.

Sadie Watson, the site director for MOLA, said: “We have entire streets of Roman London in front of us.”

At 40ft (12m), the site is believed to be one of the deepest archaeological digs in London, and the team has removed 3,500 tonnes of soil in six months.

More than 100 fragments of Roman writing tablets have been discovered. Some are thought to contain names and addresses, while others contain affectionate letters.

A wooden door, only the second to be found in London, is another prized find.

MOLA’s Sophie Jackson said the site contains “layer upon layer of Roman timber buildings, fences and yards, all beautifully preserved and containing amazing personal items, clothes, and even documents.”

The site also includes a previously unexcavated section of the Temple of Mithras, a Roman cult, which was first unearthed in 1954.

The preserved timber means that tree ring samples will provide dendrochronological dating for Roman London, expected to be earlier than the current dating of AD 47.

The artefacts are to be transported back to the Museum of London to be freeze-dried and preserved by the record, as the site will eventually become the entrance to the Waterloo and City line at Bank station.