Archaeologists uncover two Bronze Age ‘royal’ tombs lined with GOLD that promise to unlock secrets about life in ancient Greece 3,500 years ago

Historians from the classic department of the American University of Cincinnati are readdressing what is known of early Greek history based on their once-in-a-lifetime discovery of two treasure-filled tombs that were once lined with gold leaf.

The two beehive-like graves were uncovered by a team of archeologists in last year and they announced in last Tuesday in Pylos while they were investigating the tomb of the renowned Greek military leader Griffin Warrior, who had been identified with the remarkable collection of weapons armors and jewelry in 2015

The scientist Jack Davis and Sharon Stocker from the UC Classics department reported in an article on the UC Web Site that they spent 18 months excavating both graves and similarly to the Griffin Warrior’s tomb, they were called ‘princely.’

The burials were discovered overlooking the Mediterranean Sea close to the palace of Nestor, a ruler mentioned in Homer’s famous works the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Davis and Stocker´s team are excavating in Greece in the wake of the late Carl Blegen who was head of UC’s Classics Department and was responsible for having discovered the Palace of Nestor in 1939 with Greek archaeologists Konstantinos Kourouniotis.

Within the two tombs, a wealth of cultural artifacts were recovered, including delicate jewelry. As an added mark of the extreme opulence of the family, the researchers found, “The tombs were littered with flakes of gold leaf that once papered the walls.”

When interpreted alongside the artifacts recovered from the tomb of the Griffin Warrior, historians expect to use these burials to gain a deeper understanding of early Greek civilization and Pylos’ links with ancient Egypt.

Pylos is a town in the Bay of Navarino and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. It has an exceptionally long history – having been inhabited since the Neolithic era. In Classical times the site was uninhabited yet hosted the Battle of Pylos in 425 BC, during the Peloponnesian War.

Pylos was one of the last places which held out against the Spartans in the Second Messenian War and it sank out of history until the seventh year of the Peloponnesian War, during which according to the Greek historian Thucydides in his History of the Peloponnesian War, the area was together with most of the country and “round, unpopulated.”

According to Smithsonian Magazine, the identity of the ‘Griffin Warrior’ is an assumption based on the types of armor, weapons, and jewelry found in his tomb – which all suggest he had military and religious authority. It is thought that he may have been the king known in later Mycenaean times as a ‘Wanax.’

The name ‘Griffin Warrior’ was chosen after the mythological creature, the Griffin, which is composed of parts from eagles and lions, a depiction of which was found engraved on an ivory plaque in the warrior’s tomb alongside his armor, weaponry, and gold jewelry.

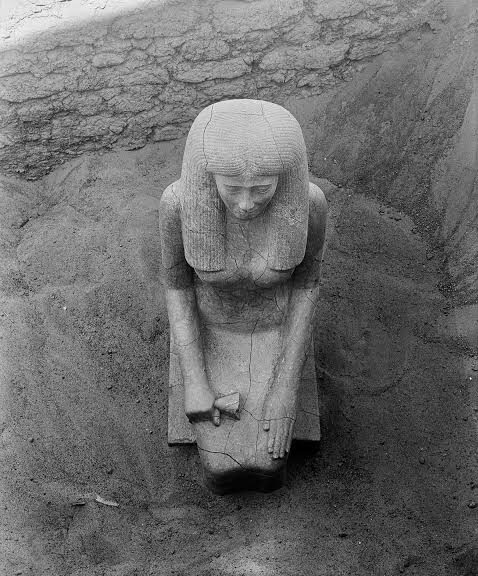

The new artifacts discovered in the two princely tombs include a gold ring with two bulls within sheaves of barley, and an incredibly detailed carnelian seal depicting an image of two ‘genii,’ which like the Griffin are lionlike mythological creatures. The depictions of the genii are shown below a 16-pointed star and they hold serving vessels and an incense burner over an altar.

According to Dr. Stocker, “16-pointed stars are rare” to find in Mycenaean iconography and he sees the discovery of two objects depicting 16-pointed stars, in both agate and gold, as “noteworthy.”

A National Geographic article says the two tombs were found holding “lots of gold” but also Baltic amber, Egyptian amethysts, and imported carnelian – which the archaeologists think belonged to “very sophisticated” people at a time when very few luxury items were being imported into Pylos – which was later a central location on the Bronze Age trade routes, said the archaeologists.

Dr. Davis said the discovery of a gold pendant displaying what might be a depiction of the Egyptian goddess Hathor is “particularly interesting considering the role she played in Egypt as protectress of the dead.” And if this is the Egyptian goddess Hathor than new evidence has been discovered suggesting early trade links between Pylos, Greece, and Egypt.