Discovery of oldest human decorations — thought to be 82,000 years old

The discovery of small perforated seashells, in the Cave of Pigeons in Taforalt, eastern Morocco, has shown that the use of bead adornments in North Africa is older than thought. Dating from 82,000 years ago, the beads are thought to be the oldest in the world.

As adornments, together with art, burial and the use of pigments, are considered to be among the most conclusive signs of the acquisition of symbolic thought and of modern cognitive abilities, this study is leading researchers to question their ideas about the origins of modern humans.

The study was carried out by a multidisciplinary team made up of researchers at CNRS, working with scientists from Morocco, the UK, Australia and Germany.

It was long thought that the oldest adornments, which were then dated as being 40,000 years old, came from Europe and the Middle East. However, since the discovery of 75,000-year-old carved beads and ochers in South Africa, this idea has been challenged, and all the more so with the recent discovery in Morocco of beads that are over 80,000 years old. The discoveries all indicate the presence of a much older symbolic material culture in Africa than in Europe or the Middle East.

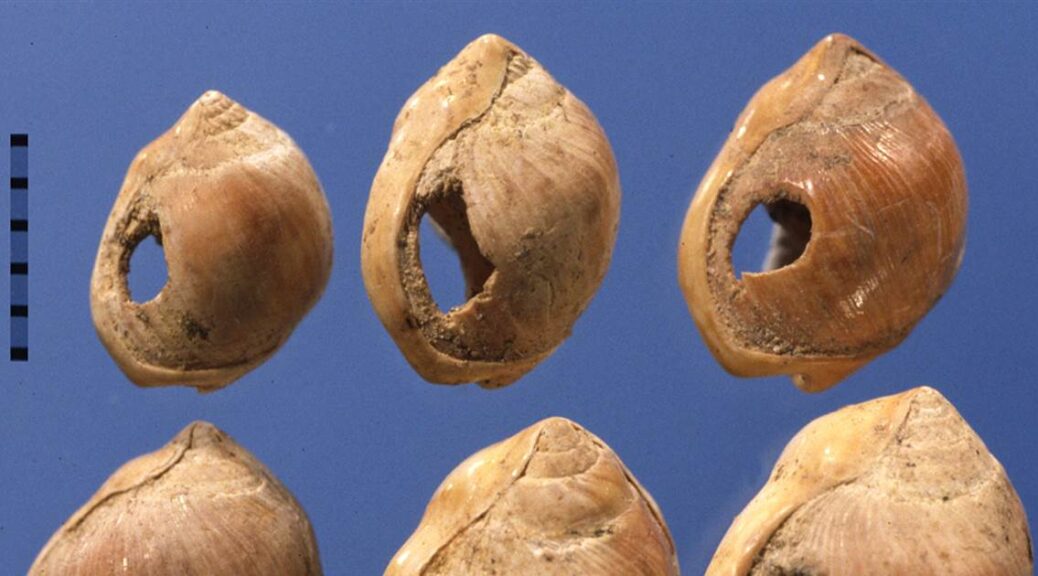

Dated at 82,000 years old, the beads, which were unearthed by archaeologists in the Cave of Pigeons in Taforalt, north-east Morocco, consist of 13 shells belonging to the species Nassarius gibbosulus. The shells have been deliberately perforated, and some of them are still covered with red ocher. They were discovered in the remains of hearths, associated with abundant traces of human activity such as stone tools and animal remains.

The mollusks were found in a stratigraphic sequence formed of ashy sediments. They were dated independently by two laboratories using four different techniques, which confirmed an age of 82,000 years.

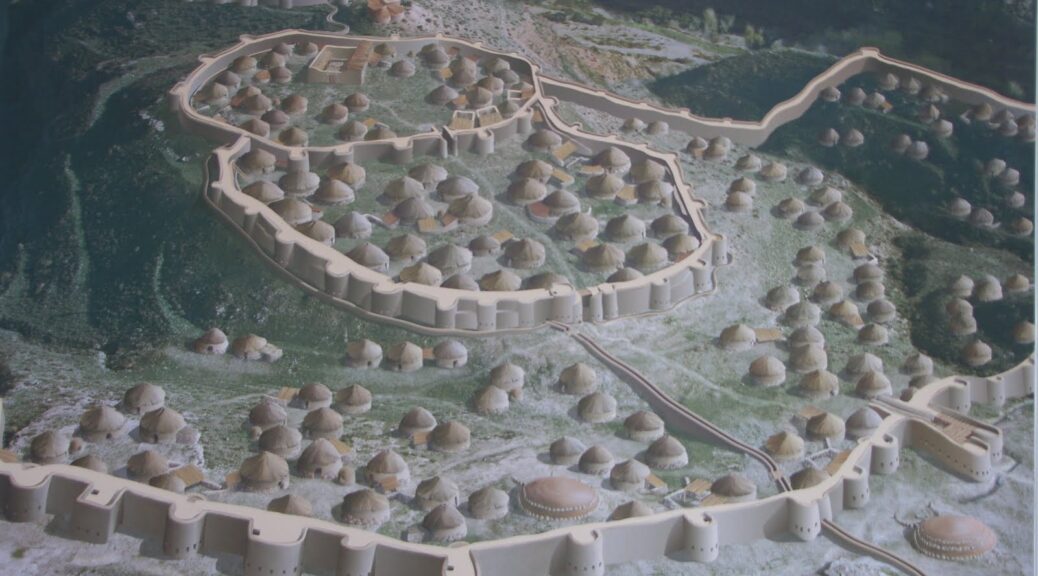

Led by Abdeljalil Bouzouggar, a researcher at the National Institute of Archaeological and Heritage Sciences (INSAP, Morocco)and Nick Barton of the University of Oxford (UK), a multidisciplinary team has been carrying out an in-depth study of the site for the past five years.

Two CNRS researchers have been especially involved in the study of the shells: Marian Vanhaeren and Francesco d’Errico, belonging respectively to the ‘From prehistory to the present: culture, environment and anthropology’ unit (PACEA, CNRS / Université Bordeaux 1 / INRAP / Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication) and the ‘Archaeologies and sciences of Antiquity’ unit (ArScAn, CNRS / Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication / Universités Paris 1 and 10).

They were thus able to reveal that the shells had been gathered when dead, on the beaches of Morocco, which at that time were located over 40 km from the Cave of Pigeons. By taking into account the distance of the coast at that time and the comparison with natural alteration of shells of the same species on today’s beaches, the two scientists inferred that prehistoric humans had selected, transported and very probably perforated the shells and coloured them red for symbolic use.

Moreover, some shells showed traces of wear, which suggests that they were used as adornments for a long time: they were very likely worn as necklaces or bracelets or sewn onto clothes.

Noticing that the beads belong to the same species of shell and bear the same type of perforation as those uncovered in previous excavations at the palaeolithic sites at Skhul in Israel and at Oued Djebbana in Algeria, Marian Vanhaeren and Francesco d’Errico were thus able to confirm the validity of these two discoveries.

Everything, therefore, seems to indicate that 80,000 years ago the populations of the eastern and southern Mediterranean shared the same symbolic traditions. To back up this hypothesis they point to other sites in Morocco where Nassarius gibbosulus beads from the same period are also found.

In addition, the two researchers point out that there is a remarkable difference between the oldest beads from Africa and the Near East on the one hand, and from Eurasia on the other. Unlike Africa and the Near East, where only one or two types of shell are found, in Eurasia from the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic onwards tens or even hundreds of different types of beads have been described.

Additional Information

1) Among the stone tools associated with the shells there are sharp biface points that are typical of Aterian technology in North Africa. They were probably used as spearheads. The animal bones were left-over food remains and are mainly identified as wild horses and hares.

2) A stratigraphic sequence is a sequence of strata.

3) These beads were attributed by the same authors to archaeological strata at the site dating back 100 000 years, based on geochemical analysis of material stuck to the shells. However, the date of the first digs at the site (which were carried out in the 1930s) made it impossible to formally prove the stratigraphic provenance of the objects. This study resulted in an article in Science in June 2006.

4) The bead found at this site came from an archaeological stratum more than 40 000 years old and was dates thanks to stone tools found in the same location: the tools are typical of the period dating from 60 000 to 90 000 years before the modern era.